I’ll never forget the moment—near the Beijing Ancient Observatory—when I was straddling my black one-speed Flying Pigeon bicycle.

It was around 1989, and I had already been in China for 5 years.

As I gazed at the observatory—it dawned on me—I was straddling two worlds; the worlds of American culture and Chinese culture.

Just a few days prior, I had learned a new phrase, 狗拿耗子 (gǒu ná hào zi); it means “the dog chasing the rat.”

My friends explained it to me as “a dog doing the cat’s job catching the mouse.”

💭 I thought of “Tom the cat chasing Jerry,” but in my mind I saw Scooby-Doo chasing Jerry instead of Tom!

I laughed out loud. 😂

Whenever I learned a new phrase, I would always use it as soon as possible to help me remember.

The next day, at work, I wanted to remind the driver—“Don’t forget to pick up the boss for tomorrow’s meeting.”

It was a perfect time to use the phrase. So, I said, “别认为我狗拿耗子,但。。。Don’t think I’m a dog catching the mouse, but...”

The driver glared at me with a red face and said, 😡 “你这么大的人怎么说这种话!How can an adult use such language?!”

I felt confounded at his response, and his red face.

Obviously, he didn’t find it humorous.

My response was simple. I had only been in China for 5 years—I was a child in terms of Chinese language and culture!

I asked a few friends what had gone wrong.

And, the answers were all the same.

The phrase is very harsh and only used in the most serious of situations—like when someone is getting involved in someone else’s business.

They couldn’t relate to my image of Scooby-Doo chasing Jerry, because it wasn’t part of their cultural psyche.

Learning the language was one thing, but learning new ways to think would change my life forever.

Take, for instance, yin and yang—or, how I say it, yeen and yahng.

Most Americans might say it means black and white, or feminine and masculine. But this is a superficial understanding. It doesn’t help us know how to apply the concept in our lives.

The concept of yin-yang, purported as discovered by the legendary first emperor 伏羲 Fu Xi, is over 7000 years old.

Fu Xi studied the positions of shadows on the ground and watched how they changed through the day. It was used as a way to tell time, like a sundial.

Deeper secrets in the shadows

Yin-Yang AKA Taiji

The early Chinese learned that when the shadow was longest, the weather was coolest—they called this “yin,” and wrote it as a broken line.

And, when the shadow was shortest, the weather was warmest—they called it “yang,” and wrote it as an unbroken line.

Fu Xi had just scratched the surface of the binary universe.

If something is tangible, there is also something intangible.

Fu Xi viewed the balance between yin and yang as a system sustaining universal order.

Noting, when one of the two energies reached a pinnacle, it flipped to the opposing energy.

物极必反 (wù jí bì fǎn)—When it reaches a pinnacle, it flips.

You know, like after you get angry or after a busy day, you end up exhausted?

Well, that’s the idea of one energy flipping to the other.

After the yang energy burns out, we need rest—yin energy.

Three ways to apply the concept of yin-yang in your life:

😞 Something negative happens

Lost your job

Didn’t get something you hoped for

Argued with someone you care for or respect

First, stop and notice the emotion.

How is it affecting your sense of self? Your relationships?

If you feel negative—yin energy—change your feelings or thoughts to positive ones; yang energy.

Apply yourself—yang energy.

Write out a list of ways to deal with the situation.

Do you feel overwhelmed or energized?

Change the flow of a certain energy by taking a cool shower or drinking a glass of water.

Perhaps you had a long, and active day—activity is yang. You may feel tired and need rest—rest is yin. Rest is the natural response to feeling depleted.

☯️ Do you ever feel caught between two worlds or opposing energies?

A good way to balance negativity is to chill.

Anger is excessive heat—yang energy. So, by adding yin, like chill energy, it cools the situation and lowers the heat.

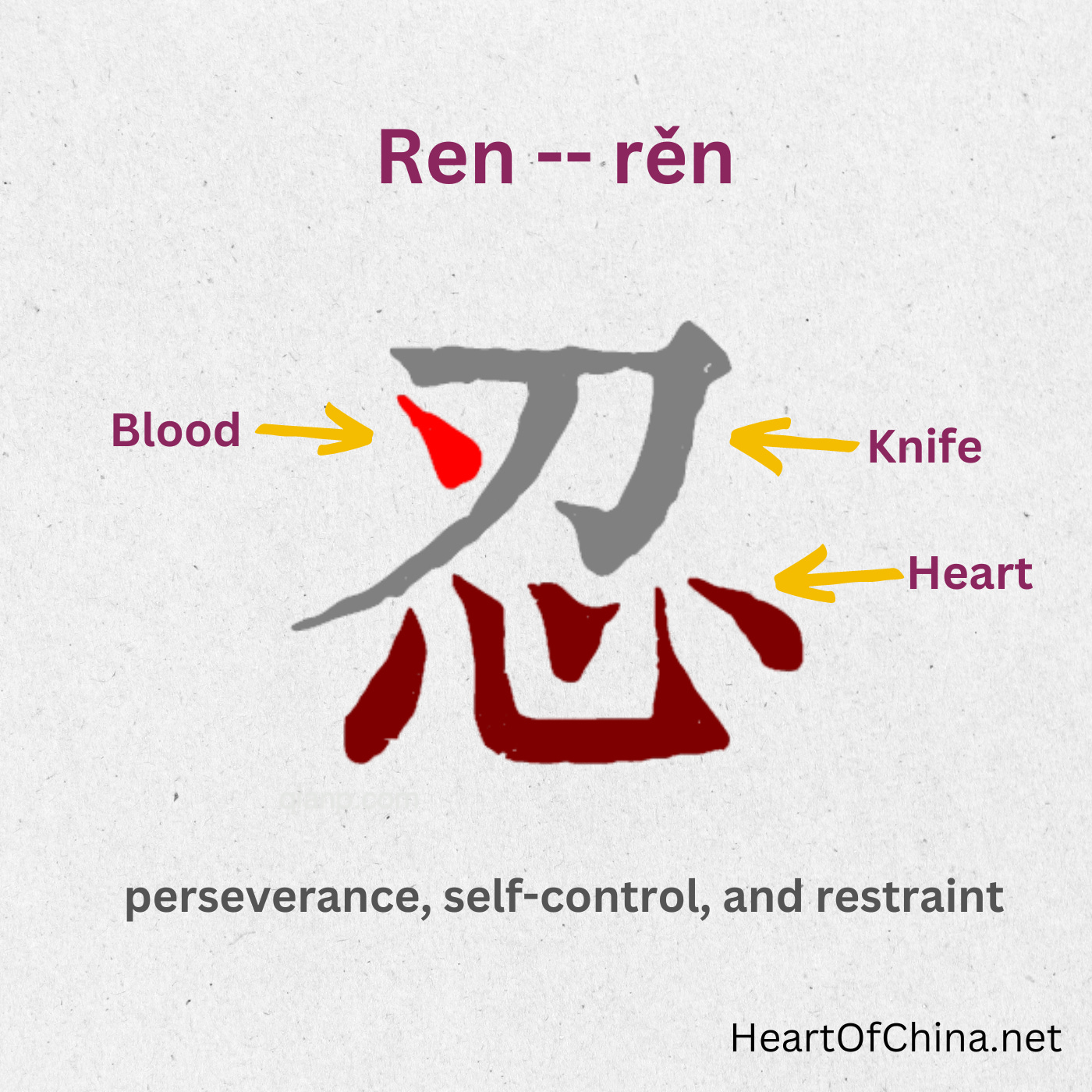

A powerful visual of “restraint” in a Chinese character

The above character offers insight into the age-old Chinese practice of applying self-control.

The character 忍—“rěn.”

The character has three decipherable character parts.

1. 刀 a knife | 2. 心 a heart | 丶a drop of blood.

The character evokes the idea of a knife cutting into a heart, with a drop of blood dripping from the knife—it is yin—a concept of coolness, introspection, and restraint.

The character conveys the ideas of such English words as, perseverance, self-control, and restraint. All of which are yin energy.

In American culture, you would think a knife cutting into a heart seems like an extreme image; but to the Chinese, it’s the image of dealing with difficulties and hardships.

Friends or family members might say, “忍一下 rěn yí xià,” to motivate someone to be strong and work through difficulties.

I remember discussing the concept of ren during a culture training for an American company. Through discussion, the people attending my training could understand its power.

The culture in our psyche

Just like the Chinese not having the cultural imagery of Scooby-Doo in their psyche, we don’t have their cultural imagery in ours!

But, when we engage our self-awareness, we balance misconceptions. If were perturbed—yang energy, we can cool down by chilling—yin energy. Appling “chill” actions—or words, will help lower the heat and take the edge off misunderstandings.

Now, I understand there are always two energies at play.

I note the prevalent energy, tap into my awareness, and adjust.

I’ve learned to apply yin energy to “chill,” and yang energy to apply myself, explore, and learn.

Then, applying yin energy again. I slow a busy mind from jumping to conclusions.

You can do this too! And you don’t need to know if it’s—yin or yang. Just notice the energy, and adjust with the opposite.

Straddling worlds

From the moment I straddled my bike, gazing at the Ancient Observatory in Beijing, I’ve contemplated these concepts.

Chinese culture is yin, introverted and subdued. American culture is yang, extroverted and outgoing. I’ve experienced the push and pull of the two within myself.

For me, being in China started like a honeymoon—everything was fascinating and exciting.

Then, when I realized how different it was at the core—social practices, interactions with strangers, and concepts of trust—I became angry and frustrated.

I wanted nothing to do with people I didn’t know. Yet, I still knew I could trust my friends.

Through the support of my friends, who helped me exit the quagmire—by explaining away my frustrations. And through my desire to understand, and continue expanding my awareness of the people, the culture, and the language—I achieved balance.

I realized—we cannot understand China through an American cultural lens.

Because we don’t evoke the same imagery. And many of the stories we tell around the same images—are not the same.

If we want to understand China and Chinese culture, we need to view them through the Chinese lens.

Once I had access to the imagery of the Chinese culture, I understood the meaning behind words and actions.

I learned to respond in ways more conducive to the Chinese status quo—but perhaps, not in line with American practices.

Watch my YouTube explainer video about “ren,” “The Biggest Weapon in the Chinese Arsenal” here.

Todd Cornell is the author of Heart Of China, How Mindfulness Changed My Life.

See my personal collection of Cultural Revolution artifacts at:

Visit my website: www.cultur668.com